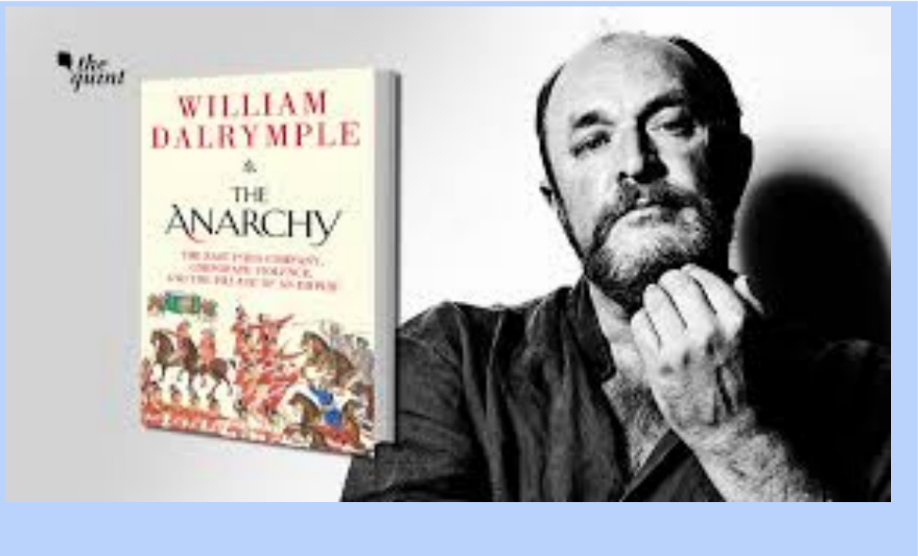

The book pictured below links the crony (noninclusive) capitalism of the past with the present. It is about the original corporate raiders variously hailed as the “greatest corporation in the world”, “the greatest society of merchants in the Universe ”, and history’s most voracious corporation—the East India Company. The author is an amazingly gifted historian cum anthropologist cum novelist. In this book, he indeed breathes passion, vivacity, and animation into historical characters so much so that distant history throws light on the rampant contemporary reality of corporate graft and crime.

It is useful to underline first what Dalrymple (2015) wrote thus: “The East India Company no longer exists, and it has, thankfully, no exact modern equivalent. Walmart, which is the world’s largest corporation in revenue terms, does not number among its assets a fleet of nuclear submarines; neither Facebook nor Shell possesses regiments of infantry. Yet the East India Company—the first great multinational corporation, and the first to run amok—was the ultimate model for many of today’s joint-stock corporations. The most powerful among them do not need their own armies; they can rely on governments to protect their interests and bail them out. The East India Company remains history’s most terrifying warning about the potential for the abuse of corporate power—and the insidious means by which the interests of shareholders become those of the state. Three hundred and fifteen years after its founding, its story has never been more current.”

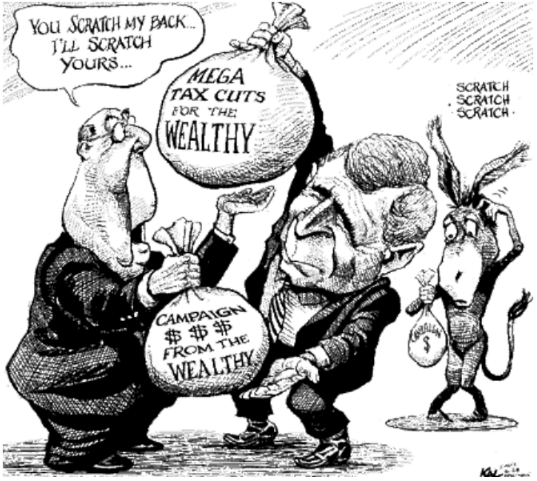

The link between business and politics has been tight everywhere since the beginning in terms of this story. As Dalrymple points out about India, the nexus between corporations and politicians that has delivered individual fortunes today rival those amassed by the sociopath Robert Clive and his fellow East India Company directors: “The country today has 6.9% of the world’s thousand or so billionaires, though its gross domestic product is only 2.1% of world GDP. The total wealth of India’s billionaires is equivalent to around 10% of the nation’s GDP—while the comparable ratio for China’s billionaires is less than 3%.

More importantly, many of these fortunes have been created by manipulating state power—using political influence to secure rights to land and minerals, ‘flexibility’ in regulation, and protection from foreign competition…Multinationals still have villainous reputations in India and with good reason; the many thousands of dead and injured in the Bhopal gas disaster of 1984 cannot be easily forgotten; the gas plant’s owner, the American multinational, Union Carbide, has managed to avoid prosecution or the payment of any meaningful compensation in the 30 years since. But the biggest Indian corporations, such as Reliance, Tata, DLF, and Adani have shown themselves far more skilled than their foreign competitors in influencing Indian policymakers and the media. Reliance is now India’s biggest media company, as well as its biggest conglomerate; its owner, Mukesh Ambani, has unprecedented political access and power. The last five years of India’s Congress party government were marked by a succession of corruption scandals that ranged from land and mineral giveaways to the corrupt sale of mobile phone spectrum at a fraction of its value. The consequent public disgust was the principal reason for the Congress party’s catastrophic defeat in the general elections.

Estimated to have cost $4.9bn—perhaps the second most expensive ballot in democratic history after the US presidential election in 2012—it brought Narendra Modi to power on a tidal wave of corporate donations…Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party is estimated to have spent at least $1bn on print and broadcast advertising alone. Of these donations, around 90% comes from unlisted corporate sources, given in return for who knows what undeclared promises of access and favours.”

Dalrymple quotes Raghuram Rajan’s speech in Mumbai expressing his anxieties about corporate money eroding the integrity of parliament thus: “Even as our democracy and our economy have become more vibrant, an important issue in the recent election was whether we had substituted the crony socialism of the past with crony capitalism, where the rich and the influential are alleged to have received land, natural resources, and spectrum in return for payoffs to venal politicians. By killing transparency and competition, crony capitalism is harmful to free enterprise, and economic growth. And by substituting special interests for the public interest, it is harmful to democratic expression.” These “anxieties were remarkably like those expressed in Britain more than 200 years earlier when the East India Company had become synonymous with ostentatious wealth and political corruption.”

As a consequence, how the British government seized India by bypassing the East India Company which seized India first and ruled the roost for a hundred years, is a story worth reading in Dalrymple’s book. And earlier, how one of the world’s most magnificent empires, the Mughal Empire, disintegrated and came to be replaced by a dangerously unregulated private company, based thousands of miles overseas in one small office, five windows wide, and answerable only to its distant shareholders, is also a remarkable storytelling indeed. The colourful photographs given in the book speak for themselves the deception and candour of the past.

The conclusion of Dalrymple is rather disturbing: “The 300-year-old question of how to cope with the power and perils of large multinational corporations remains today without a clear answer: it is not clear how a nation-state can adequately protect itself and its citizens from corporate excess…Corporate influence, with its fatal mix of power, money, and unaccountability, is particularly potent and dangerous in frail states where corporations are insufficiently or ineffectually regulated, and where the purchasing power of a large company can outbid or overwhelm an underfunded government.”

As Sikka (2008) corroborates about Britain as the sleaze capital of the Western world, “Corporate bribery and corruption destroy social fabric. Yet governments and regulators continue to see bribery and corruption through the prism of corporate interests and do little to inconvenience them. Perhaps, political parties do not wish to damage their chances of securing corporate donations, and regulators do not wish to damage their chances of securing future employment with the same companies.”

Contemporary crony capitalism is associated with labour repression. For example, an Argentine study has shown that the corporates benefitted from violence against labour union representatives by subsequently having less strikes and a higher market valuation. Which is also the reality in India and many other countries.

There are numerous articles and books on crony capitalism in different parts of the world. For the Indian context, read further, for example, the economist Bardhan (2023) and management professors Khatri and Ojha (2017).

References

Bardhan, Pranab (2023). Unmasking India’s Crony Capitalist Oligarchy. Project Syndicate. February 13.

Dalrymple, William. 2015. The East India Company: The Original Corporate Raiders. The Guardian. March 4.

Khatri, Naresh and Abhoy Ojha (eds.) (2017). Crony Capitalism in India. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sikka, Prem. 2008. The Capital of Corporate Corruption. The Guardian. June 27.

By Annavajhula J.C. Bose, PhD

Department of Economics, SRCC