The Performance of Girlhood

Recently, I watched a movie called My First Summer. It is about a troubled young girl meeting a spirited counterpart, and their time together spanning over one whole summer. My First Summer was fascinating. It is a beautifully shot movie, with wide-angled shots and aesthetic yellow lighting. But it is not enjoyable simply for the fact that my gallery is full of stills from it. Instead, it is gorgeous because it is an island. Each frame is laced with intimacy. The film is gorgeous because there is nobody else except those two girls, holding each other’s hands through the night. No one is watching them. More specifically, no men are watching.

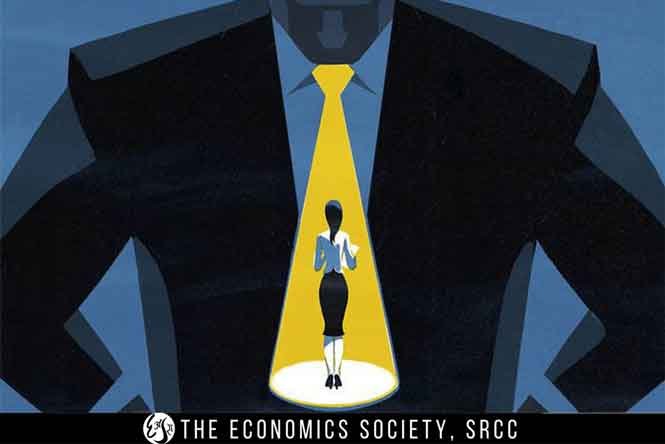

The Perpetual Onlooker

The Objectification Theory by Fredrickson and Roberts proposes that in a culture that sexually objectifies women's bodies, girls and women start to adopt an observer's perspective to monitor their bodies, that is to engage in self-objectification. Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) proposed that these experiences usually begin at the transition from childhood to adolescence, as girls' bodies begin to attract the public gaze, sexualisation, and evaluation of others. Furthermore, they proposed that women's disproportionate rates of depression and eating disorders may be explained in part by experiences related to sexual and self-objectification. When I step out of my house to buy a pen, I am aware of all the men around me. While deciding what to wear for those ten minutes, when walking down the road and while talking to the shopkeeper, I am always analysing how those men are perceiving me. These thoughts persist when I am in school, when I raise my arm to answer a question, when I’m all alone in my room. It is inescapable.

Empowerment vs Sexualisation

Today, we’ve reached a junction where anything a woman does is termed as a product of patriarchy or a revolution in and of itself. Capitalism and patriarchy are intertwined. But as feminism gains more traction, the economy must figure out a way to profit from it. In her 2009 book, ‘One-Dimensional Woman’, Nina Power writes, "Images of a certain kind of successful woman proliferate," "The city worker in heels, the flexible agency employee, the hard-working hedonist who can afford to spend her income on vibrators and wine--and would have us believe that-yes-capitalism is a girl's best friend.

In the Indian context, a study was done by students at NMIMS on the efficacy of feminism advertising or ‘femvertising’. The purpose of the study was to understand the impact of femvertising ads on the purchase intention, brand equity, attitude towards the ad, persuasiveness towards the ad and self referencing with the ad. An experiment-design study was conducted, in which consumers were requested to participate in a study regarding advertising perceptions. The participants were 160 graduate and undergraduate students aged 18-34 years from diverse study backgrounds like management, advertising, liberal arts, law and engineering studying in Narsee Monjee School of Management Studies, Mumbai. Their findings supported the thesis that women’s self-concept today has changed to one of self-empowerment and reliance on their own decisions.

So, advertisements that align with this self-image are likely to draw more female consumers. The study’s conclusion urges marketers to consider using femvertising to “attract more consumers, leading to higher revenues.” In her thesis ‘Selling Empowerment: A Critical Analysis of Femvertising’, Alexandra Rae Hunt uses feminist critique from a third-wave perspective to qualitatively analyse three different ‘femvertising’ campaigns: Dove’s “Campaign for Real Beauty,” Always’s “Like a Girl” campaign, and Pantene’s “Shine Strong'' campaign. She concluded that although femvertising gradually leads to shifts in female perception in society, the campaigns have ambiguous motives. Dove’s campaigns try to paint a picture of what a “real” woman looks like, however in this attempt, Dove also excludes many identities, especially – and one may argue more aggressively – those who actually do fit into traditional beauty standards.

Pantene promised to empower women, and yet equated skinny bodies, flawless skin and long, shiny hair with happiness and success. The visuals propagated in femvertising lack depth and critique. The varying experiences of women of colour, women in the LGBTQIA+ community, women in poverty are rarely spoken about, since this is unmarketable for brands. PHD Media, a media and communications firm recently released a quantitative survey of women aged 18+ across the U.S., “to identify when women feel most vulnerable about their appearance throughout the week in order to determine the best timing for beauty product messages and promotions.”

The firm conducted a series of 30 minute interviews with these women, selected from a proprietary US panel. 648 respondents were surveyed over a span of two days in the spring of 2013. Survey contained questions related to the moments when respondents felt most vulnerable about their appearance and attractiveness. Overall, women across all demographics(urban, suburban, rural, young, old) had strong commonalities when it came to feeling vulnerable about their beauty. Almost half of the participants (46%) say that they feel least attractive on Mondays. The firm suggested concentrating media during “prime vulnerability moments.”

In her study on Contemporary Consumer Feminism, Kate Hoad-Reddick submits, “Dove figured out that the best way to sell products to women with chronically low self-esteem is to address the pervasiveness of how much they dislike their bodies. If 98% of Dove’s market do not consider themselves beautiful, it seems logical to sell them just enough feminist empowerment to convince them that Dove, with its awareness-raising mandate and skin-firming lotions, is the answer to their unhappiness. A splash of feminism will make the body wash sell.” So we’re handed packaged one-liners, catchy slogans, bright posters and artsy t-shirts. And the world goes on. If a girl wears a short, tight, revealing dress with glittery eyeshadow, is she giving in to her own sexualisation? Or is she subverting the male gaze and choosing what she wants to wear as an act of empowerment? I asked a friend this question, and he rolled his eyes at me.

He said, “Why do you have to complicate things so much? If she’s wearing it for guys, she’s being complicit, if she’s wearing it for herself, she’s not.” This brings me to my next point. Why do I have to complicate things so much? It is because the entire self-image of one gender has been intrinsically tied to the desires of another. It is because of the fact that if you ask that girl with her shiny purple eyeshadow why she feels prettier with makeup on, she won’t have an answer. Why do I have to complicate things so much? It is because dressing boldly is women’s way of establishing independence over their bodies. It is a retaking, and a reimagining of how their stories have been painted for centuries. Yes, it is simple to think of it as black and white. It is easy for my friends to convince themselves they like to dress up for themselves. And it is easy for me not to press them further, easy not to ask, “But why? Why does looking pretty matter in the first place?” These are important questions, though. How much of women’s self-image is dictated by male preferences? How much autonomy do they truly have?

Does the mere ability to choose imply empowerment?

The Myth of Choice

A lot of feminist media emphasises on the power of the choice. We do not live in a vacuum, and to attribute actions simply to a woman’s choice to perform them would be assuming we no longer live in a patriarchal society. The system in place definitely affects our decision-making, and needs to be acknowledged as a factor. In The Sexual Liberals and the Attack on Feminism, Catharine MacKinnon, in a piece titled ‘Liberalism and the Death of Feminism’, posited that liberalism is the very antithesis of a movement for women’s liberation. Natalie Jovanovski writes in ‘Freedom Fallacy: The limits of liberal feminism’ that, Individualism lies at the heart of liberal feminism, championing the benefits of ‘choice’ and the possibility that freedom is within reach, or occasionally, that it already exists should women choose to claim it. It also pushes – sometimes overtly and sometimes covertly – the fallacy that substantive equality has already been achieved and that the pursuit of opportunity lies solely in women’s hands. ‘Right to choose’ does not mean giving in to oppressive systems of objectification. Giving in to self-objectification is not true freedom. Our study of ‘choices’ must consider social and political contexts. When I was about twelve, I read a lot of romance novels. They were all mostly the same; the quirky, eccentric female protagonist meets a bad-boy love interest. I enjoyed imagining myself in her place, because I felt like an outsider in school too. I would spend hours analysing what the “pretty girls” were doing right. I had to attack their every display of femininity and feel better about myself by distancing myself from it. Do you understand?

I had to feel less like what I thought all the other girls felt, in order to believe I had some sort of value.

Four years later, I recognised this habit. I recognize that instinct. It is something I still have, something I still feel the need to consciously suppress. The lines between how I want to be viewed, and who I really am, have become so blurred that I cannot identify a single thing I do and say, “That’s something I’m doing for just me.” The scariest thing about the male gaze is its ubiquity, and its invisibility. In The Second Sex, Simone de Beavoir states: “Women are complicit in their own oppression. In existentialist terms, women internalise the male gaze, and with it the expectations of the gender. They are conscious of how they are observed, and women’s own thinking assimilates this awareness.”

” Here’s a Bojack Horseman quote I came across recently: I do wonder as a third-wave feminist if it is even possible for women to “reclaim” their sexuality in this deeply entrenched patriarchal society. Or if claiming to do so is just a lie we tell ourselves so we can more comfortably cater to the male gaze. So, how do we navigate self-expression and personal identity amidst constant internal and external surveillance? There is no one-step solution to the internal male gaze, much like how there is no one-step solution to the patriarchy or any of the other issues I discussed. The first step is to acknowledge the larger picture. Compassion is essential, both for our own selves and for others. The next time you feel the need to look attractive when you are all alone at home, remind yourself you are not on stage. We are not machines . You do not need to perform for anyone. Maybe it is time to indulge in being the looker instead.

Pragya Tomer

High School Student

References

An Enquiry Into Internalised Male Gaze: Whose Camera Is It Anyway? (2020, December 3). Feminism in India. Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://feminisminindia.com/2020/10/14/male-gaze-camera-internalized-patriarchy/

Just a moment. . . (n.d.). Retrieved October 14, 2022, from

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258181826_Objectification_Theory_Toward_Understanding

_Women's_Lived_Experiences_and_Mental_Health_Risks

PHD Media. (2018, June 30). New Beauty Study Reveals Days, Times And Occasions When U.S.

Women Feel Least Attractive. Retrieved October 14, 2022,

from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-beauty-study-reveals-days-times-

and-occasions-when-us-women-feel-least-attractive-226131921.html

Faludi, S. (2013). Facebook Feminism, Like It or Not.

The Baffler, 23, 34–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43307858

Does femvertising matter? A study in the Indian context. (2019, March). Http://Ijrar.Com/, 6(1),

Article 20543438. http://ijrar.com/upload_issue/ijrar_issue_20543438.pdf

Hunt, A. (2016). Selling Empowerment: A Critical Analysis of Femvertising. Boston College University Libraries.

Hoad-Reddick, K. (n.d.). Pitching the Feminist Voice: A Critique of Contemporary Consumer Feminism. Scholarship@Western. Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5093/

Tyler, M. (2015, April 26). Freedom Fallacy: The limits of liberal feminism. Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://www.academia.edu/11364148/Freedom_Fallacy_The_limits_of_liberal_feminism

Tyler, M. (2015b, April 29). No, feminism is not about choice. The Conversation. Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://theconversation.com/no-feminism-is-not-about-choice-40896

Murphy, M. (2018, March 5). The trouble with choosing your choice. Feminist Current. Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://www.feministcurrent.com/2011/03/11/the-trouble-with-choosing-your-choice/

Ammann, J. (2020, May 19). The Myth Of Choice Feminism. Women’s Republic. Retrieved October 14, 2022, from https://www.womensrepublic.net/the-myth-of-choice-feminism/